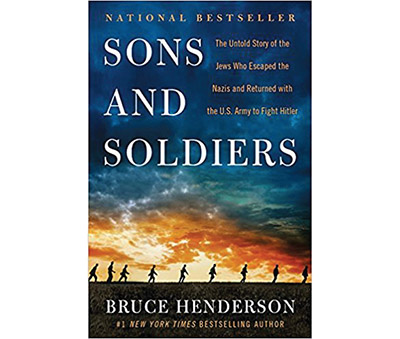

The Beth Aaron Book Club, currently led by Diane Fogel, has been reviewing Jewish-related fiction and nonfiction since 2000. At the last meeting, in preparation for the next selection, the title “Sons and Soldiers” was suggested by Esther Schnaidman at the recommendation of her mother. The 2017 historical work by New York Times bestselling author and historian Bruce Henderson documents the stories of six of the almost 2,000 young Jewish refugees who escaped the Nazis only to return with the US Army to fight Hitler as members of a covert intelligence corps called The Ritchie Boys. Flipping through the list of Ritchie Boys provided by the author at the end of the book, Nancy Friedman, a book club member, was astonished to see the name of her father, Ernest A. Joseph. Debbie Ross, also a regular club member, recalled that her uncle Edgar Rauner, had also served as a Ritchie Boy. With these two connections in mind, and the popularity of the work, it was decided to open the book discussion to the entire Beth Aaron community.

Last week, close to 30 people joined Fogel and Schnaidman in a lively discussion of “Sons and Soldiers.” In the audience was Judge Lee Blech First, mother of Beth Aaron member Mitchell First, who was drawn to the book club meeting after discovering that her own story of coming to America at age 13 was recorded in the book as it was identical to the story of one of the six Ritchie Boys highlighted in the book.

Of the millions of American men who fought in Germany during World War II, only a minority were of Jewish extraction and of those only a miniscule number were of German birth. “Sons and Soldiers” focuses on this veritably unknown minority of young men who managed to be squirreled out of Europe in the 1930s through the ingenuity of their families and escape to the US. In mid-1942, the US Army began to recruit and train these select individuals through an eight-week-long training program at the newly constructed $5 million hush-hush facility in rural Maryland known as Fort Ritchie. Here these ethnic German Jews, who spoke German as well as other European languages, were trained as translators and interrogators. As they became expert in the fine art of eliciting critical intelligence information from captured German POWs, they were assigned to frontline Army units in Europe. Known as Ritchie Boys, they were promoted rapidly and placed on the fast-track to citizenship. Sent into dangerous war zones, often at great risk to their lives, these Ritchie Boys were able to elicit critical tactical information that contributed to US battlefield victories and resulted in saving thousands of US lives.

In the immediate post-war period, the Ritchie Boys remained in Europe with their units and continued their work through the numerous “street meets” between SS/Gestapo members and thier victims. The program was shut down in 1948, but between the war’s end and the cessation of the program, the Ritchie Boys utilized their rank and position to try to trace the fates and wherabouts of their own family members. Although some did succeed in finding family members, others learned of their deaths from abuse, disease or gassing.

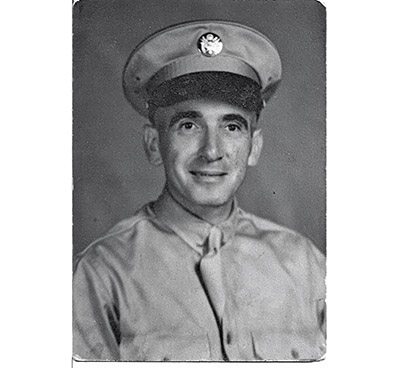

At the book club discussion, Nancy Friedman and brother Henry Joseph shared that they had never heard their father Ernest Joseph talk about his involvement as a Ritchie Boy. What they did know was that their father, born in Germany, came to the US in 1928 at the age of 19. He attended college under the quota system. He spoke English fluently, without a trace of a German accent. He was inducted into the US Army in April of 1942 and discharged in November of 1945. Of the little they heard from their father, he worked under a General Clark in the 5th Army Division, which traveled through Italy and North Africa. They knew that part of his work was interrogating Nazis. Their favorite story was that once when interrogating a complicit Nazi, the Nazi broke into a venomous tirade about how horrible Jews were. In an impetuous response, Joseph slapped the Nazi across the face, at which point the Nazi demanded to see Joseph’s commanding officer. When General Clark was called in and heard the accusation, he proceeded to slap the Nazi across the face—twice. They both recalled their father telling them that after the war, General Clark converted to Judaism.

Debbie Ross came to the book discussion with a detailed account of her uncle Edgar L. Rauner’s experience as a Ritchie Boy. It had been compiled by another uncle, Wolfgang Rauner, who resides in Forest Hills. Edgar Rauner arrived in the US in 1941 and was able to obtain work as a pastry chef as he had been trained in Luxemberg. On April 6, 1943, he was inducted into the US Army and granted US citizenship. While serving in Texas as an army baker, he was recruited into the Ritchie Boys and trained as an interrogator and interpreter based upon his fluency in German. The account goes on to detail his travels through Europe with as much detail as he was allowed to share in letters to his family. After the war, he remained in Germany until March 18, 1946, when he was honorably discharged.

Judge Lee Blech First came to the US as a 13-year-old together with her parents Rabbi and Mrs. Benzion Blech and her siblings. Escaping through Switzerland and France, they arrived in Seville, Spain, to finally embark upon the final leg of their journey to freedom. When First read the account of Ritchie Boy Victor Brombert’s transport to America with his family aboard the Spanish shipping vessel the SS Navemar, she became aware of the tribulations of her own family’s passage to America on the same ship. The SS Navemar was a freighter with passenger accomodations for only 28 people. As it was one of the few available vessels for desperate European refugees; the fee for passage was scandalously priced at $1000 per person. Nevertheless, the cargo hold was soon filled “not with bananas or coal” but with 1,120 refugees from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. The zigzag course taken to avoid German U-boats took six long weeks. The passengers slept on lifeboats or in dark, airless holds filled with the stench of human waste. Many people fell ill with typhus and dysentary. Six were buried at sea. Local newspapers referred to the ship as “a floating concentration camp.”

Judge First, author of a memoir entitled “Justice Is Blond,” served as a judge in workmen’s compensation court for 12 years under Governor Hugh Carey. Trained as a lawyer, she worked alongside her husband for 20 years before assuming her judgeship. She descends from 10 generations of rabbis and was one of the first students to attend the Bais Yaakov of Boro Park.

By Pearl Markovitz