The Jewish people have always treated their sacred objects with respect even when they are worn out and no longer usable. Instead of throwing them into the garbage amidst ice cream containers and banana peels, we put our holy objects in genizah (storage for later burial), or what is more colloquially known as sheimot (or sheimos). Disposal of sheimot has become more complicated in modern times due to the widespread proliferation of materials with Torah content, about which there is a range of halachic opinions regarding their status.

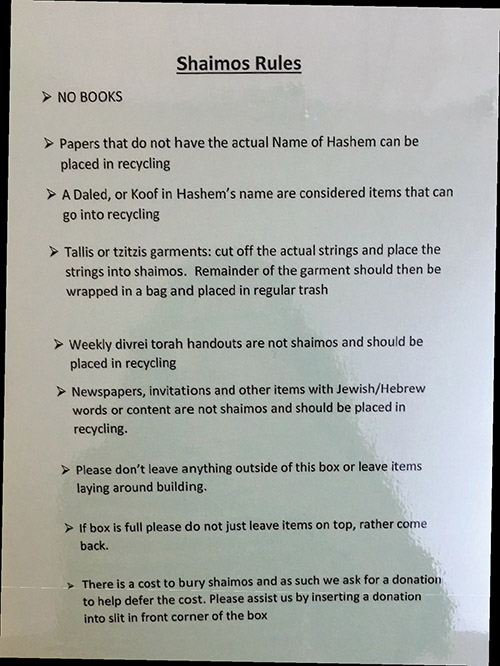

One example is found in Teaneck’s Congregation Bnai Yeshurun, which has a sheimot box on the first floor of the shul with a sign stating specific policies about what should and should not be placed in sheimot (see photo). Other institutions may have different policies based on different halachic opinions. Some examples of CBY’s policies are: “Papers that do not have the actual name of Hashem can be placed in recycling. A daled or koof in Hashem’s name are considered items that can go into recycling. Weekly divrei Torah handouts are not sheimos and should be placed in recycling. Newspapers, invitations and other items with Jewish/Hebrew words or content are not sheimos and should be placed in recycling.”

Where does one put sheimot? Some local shuls offered information for this article about their sheimot services (but of course, contact your shul for more information). Executive director of CBY Elysia Stein explained that in addition to the sheimot box “We do a specific drive, once or twice a year, where we are better able to enforce the rules. Unfortunately, at the box itself we are really just relying on people reading the rules, understanding them and following them.”

However, people do not always follow the rules and leave the shul with objects and printed materials that CBY does not consider to be sheimot, which wastes the shul’s resources. CBY stores its sheimos in various places on its property until it is collected. Stein concedes, “Storage can definitely be a challenge, but we do our best. If we have too much to store we would have to call an additional sheimos collector and pay additional funds to have it taken away immediately.” Stein continues, “We have a dedicated volunteer who reviews the material to ensure it is actually sheimos.” CBY requests donations to help defray the costs.

Congregation Beth Abraham allows people to drop off sheimot at their office at $12 per supermarket bag and $20 per garbage bag. They do not have specific policies about what they collect. They also host a collection drive twice a year on a Sunday around Pesach and around High Holidays, as does Congregation Rinat Yisrael. Shaarei Orah has a box in their office where people can drop off sheimot as needed all year round, but do not have specific guidelines. They request $18 donations per bag/box as well.

To avoid creating sheimot unnecessarily, Moshe Kinderlehrer, publisher of The Jewish Link, noted that when he first began the paper he got a psak that he could print Torah content on newsprint because it is not sheimot. However, occasionally, if pictures with actual names of God, such as a Torah scroll, accidentally make their way into the paper, that is considered sheimot. These situations are avoided at all costs, with multiple safeguards in place to avoid mistakenly placing God’s name in the newspaper, said Elizabeth Kratz, The Jewish Link’s editor.

Most of the shuls do not dispose of the sheimot themselves. Two or three times a year, Shaarei Orah gives their sheimot to Rabbi Yitzchak Weinberger of soferlinks.com in Lakewood, New Jersey. Rabbi Weinberger, in addition to doing kiruv in the Center for Jewish Identity in Bergen County, is also a sofer (scribe). Part of the job description of being a sofer is checking mezuzot and tefillin, which is how he got involved in collecting sheimot in the first place. He explains, “As a sofer, I generate a lot of sheimos, and most of what I get is a byproduct of mezuzah checking. I check tefillin and mezuzos about 10 times a year in different shuls in Teaneck, Fair Lawn and Englewood and people can bring me other sheimos then. I also collect larger quantities of sheimos by appointment as well and I can do pick-ups from houses.”

Besides just collecting old mezuzot and tefillin, Rabbi Weinberger has had some more unique experiences. “Someone once brought me an aron kodesh that was directly used for a sefer Torah; it had kedusha and could not be thrown in the garbage. That was a big job.” As sefarim are ideally supposed to be re-used if possible (not buried), Rabbi Weinberger looks through the sheimot he receives and builds his own sefarim collection from it. One time he found a treasure: “I was involved with an old couple who was downsizing and the fellow gave me a bunch of his old sefarim. It was a small job, just a box of bentchers and a few old sefarim. One sefer he gave me was a 150-year-old Baer Mayim Chaim, a popular chasidishe sefer, which it turned out was valued at at least $800. I asked a shailah. I was told to return it, which I did.”

Rabbi Weinberger give the remaining sheimot to 1866shaimos in Lakewood, New Jersey, a company run by Rabbi Aaron Taplin. Rabbi Taplin also collects the sheimot for many of the local shuls in North Jersey directly. For example, after Rinat and Beth Abraham have their sheimot drives, he drives up the next day from Lakewood to collect the materials. The busiest time of year for him is Pesach, but all year round they help individuals who are downsizing and are involved in clearing homes of people who have passed away. Rabbi Taplin’s main focus is actually second-hand books; burying sheimot was just an outgrowth of that. He started Capital Sefarim, a second-hand sefarim store, with branches in Lakewood and Monsey and a large variety and quantity of sefarim.

Rabbi Taplin is proud of what they do. “It is really a tremendous accomplishment that we are able to save all these sefarim and pass them on. I can’t tell you how many people we’ve helped empty out their house or apartment, who are giving away sefarim they venerated for so many years. Often they are worried about what will happen to them, and want to hear that other people are going to use their sefarim. Before the school year every kid comes in with a list of sefarim he needs and they are able to buy it from 20 to 70 percent off regular price.”

Although he manages to save many sefarim, the amount of sheimot Rabbi Taplin must bury grows every year. He explains, “Years ago it was a lot easier to save a lot more, but as time goes on people become picky and there is more availability of nicer sefarim. In turn, we have to be picky in terms of what we are going to keep and what we are going to bury.” In fact, they bury 50 trailer loads a year. “The sheer number of sheimos is mind-boggling,” says Rabbi Taplin.

All this sheimot must be buried in a way that preserves it as long as possible, since the point is to postpone its disintegration. Rabbi Taplin explains: “When sheimos gets buried, it needs to be done in a way that is the least damaging to the sefarim and other holy objects we bury. We put the sefarim and papers in polyethylene bags because that preserves them the most. We also line the hole in which the burial takes place.”

“People think, ‘Oh what’s the big deal? You just open up a hole, put in the sheimos and you’re done,’” says Rabbi Taplin, “but it is not that simple.” Besides for the halachic aspects, sheimot burial must be done legally, which is made complicated by the Department of Environmental Protection. The DEP is not enthusiastic about the burial of large quantities of paper because they want to recycle it, and therefore they require special permits that are difficult to access. In fact, there have been a number of scandals by other sheimot companies in the past where sheimot was dumped in landfills and other illegal areas. Rabbi Taplin explains that 1866shaimos “has worked for 23 years with the DEP to bury sheimos according to law.”

Purchasing land to bury sheimot is also expensive, which is why Rabbi Taplin does not want to mention exactly where the sheimot is buried. He worries that it would invite trespassers who would try to bury their sheimot on his plots. The DEP does not allow burial in heavily populated areas, and the land is cheaper away from population, so the plots are not nearby.

Just as Jews confirm meat is kosher through a hechsher, people also use hechsheirim to sanction halachic sheimot burial. 1866shaimos has two hechsherim, one from a local rav in Lakewood, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Friedman, the other from the Satmar beis din. Rabbi Taplin explains: “We live in Lakewood so we used a local rav, who knows us. Regarding Satmar, we are not officially affiliated with Satmar. However, the Satmar community in Williamsburg is one of our biggest customers; they give us four or five trailer loads of sheimos a year. Even though we have our own local hashgacha, they wanted their own beis din to also give a hashgacha; they are exacting and have very high standards.” Rabbi Taplin says that they have also gone in front of other communities’ batei din (rabbinic courts) to prove their kosher sheimot practices, although those communities don’t all officially give out hechsherim as Satmar did.

The Mishna in Pirkei Avot 4:6 quotes R. Yosi: “Whoever honors the Torah is himself honored by the people.” An important way to fulfill this dictum is by being careful with and increasing our awareness of the issues surrounding sheimot and sacred objects.

Disclaimer: Nothing mentioned in this article should be taken as a halachic psak. Please ask your own rabbi if you have questions.

By Sara Schapiro

Sara Schapiro is a rising sophomore at Stern College for Women and a resident of Bergenfield.