Part 2

(continued from last week)

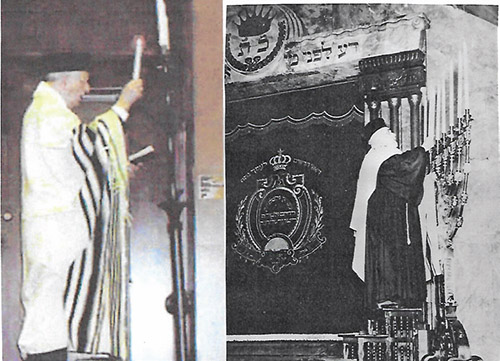

I include here a picture of Chazan Frankel during candle lighting on Chanukah. It reminds me of my youth, since the lighting, especially of the first candle, was a big affair at KAJ. Everyone came to shul, young and old. It was especially exciting for children to watch Bob climb up the three steps (believe me there were three steps even if not shown in the picture), candle held high and starting to say the brachot. This was the tradition brought over from Frankfurt.

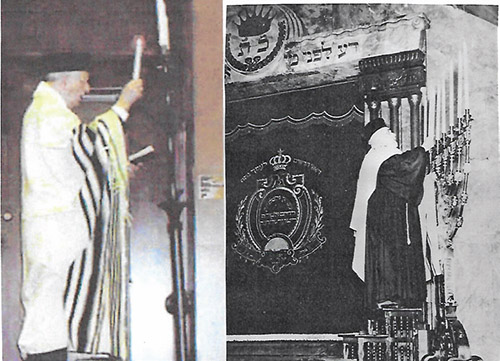

As a comparison I also include an almost parallel picture of the famous Chazan Pessachowitch lighting the candles in Frankfurt. See the three steps and also the Dah lifneh mi ato omed, all setting the example copied by Breuers in their shul.

(“Why I daven with the Yekkes” continued from last week)

From the first time I set foot in K’hal Adath Jeshurun (also called Breuers), it immediately made sense to me. It seemed to me that this was exactly what a shul was supposed to be like. The decorum, the choir, the strong sense that everyone knew what to do and the beauty of the shul itself all had something to do with it. But looking back, I think a lot had to do with Chazan Frankel. When I went back this year to spend Rosh Hashanah in Washington Heights, so many things reminded me of why I strongly believe that our religious lives would be richer if we had more shuls like this. Chazan Frankel embodied much of that, and my thoughts drifted to him as I opened my machzor on erev Rosh Hashanah.

I had heard Chazan Frankel daven for a number of years before I ever talked to him. He was tall and regal in his bearing. His voice was pleasant, but not the kind of voice that comes to mind when most people hear the word “chazan”—for German chazanus is very plain, not fancy and operatic like Eastern European chazanus. (In fact, Yossele Rosenblatt left his position in Hamburg because his style was too ornate for them!) Chazan Frankel would pass my seat as he proceeded from his seat to the amud, never smiling, never talking to anyone, tallis draped over his arms and hanging down in the German fashion, davening from Adon Olam at the beginning until Anim Zemiros at the end. He certainly never said hello to me, and, I have to admit, I assumed he must be—to put it nicely—cold, aloof and standoffish. I even think I was a little scared of him, the way a young child might be scared of a mean old man.

One week, Mrs. Frankel invited me for dinner on Friday night. She worked in the finance office at Yeshiva University and loved to invite “the boys” over for Shabbos. (This grandmotherly “little old lady” later confided to me that she frequently carried $10,000 cash in her purse across Amsterdam Avenue!) I was intrigued but more than a little nervous about having to spend several hours in dark, dour silence. When Friday night came, outside of shul after davening, I introduced myself to Chazan Frankel. Two things shocked me about that first meeting. First, I realized I had never heard him speak English before, and he spoke with a heavy German accent, which just didn’t seem to come across in his Hebrew at the amud. But even more shocking was that he had a sense of humor! He told me a joke! (I eventually came to learn that he had quite a good sense of humor, even a little impish at times.) He was warm, and he joked! So, Friday night turned out to be quite a fine evening, the first of many memorable Shabbos evenings with a lot of guests at his table.

On my way home that night, I must have tried to reconcile the two Chazan Frankels: the one in shul, and the one in the street. I assumed that his demeanor at the amud was a put on, like a stage personality.

But as I got to know Chazan Frankel, I slowly realized that nothing could be further from the truth. I began to understand the essence of what it means to daven before the amud, the kind of things you can never learn from a “learn-how-to-daven-Mussaf” CD. From the moment he left his seat to make the walk to the amud, it was all business. The absolute dignity and seriousness required to stand before one’s Maker demanded no less. He walked with a certain formality, a solemn procession of one. He stood tall, tallis draped over his arms, almost touching the ground, ready to make his offering to Hashem in the only way a human can, with ephemeral vibrations of sound that fill empty space and then are gone. He pronounced every word correctly, and with care. I never saw him slouch or lean on the amud. He never wandered from the amud or stepped away from it, unless required to do so by the service. In over 50 years, he was never once late for shul when he had to daven.

(To be continued next week)

By Norbert Strauss

Norbert Strauss is a Teaneck resident and Englewood Hospital volunteer. He frequently speaks to groups to relay his family’s escape from Nazi Germany in 1941.